July, 1969

It’s JUST over eight years since the flights of Yuri Gagarin and Alan Shepard, followed quickly by President Kennedy’s challenge to put a man on the moon before the decade is out.

It is only seven months since NASA’s made a bold decision to send Apollo 8 all the way to the moon on the first manned flight of the massive Saturn V rocket.

Now, on the morning of July 16, Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins sit atop another Saturn V at Launch Complex 39A at the Kennedy Space Center. The three-stage 363-foot rocket will use its 7.5 million pounds of thrust to propel them into space and into history.

OFF TO THE MOON

At 9:32 a.m. EDT, the engines fire and Apollo 11 clears the tower. About 12 minutes later, the crew is in Earth orbit. After one and a half orbits, Apollo 11 gets a “go” for what mission controllers call “Translunar Injection” — in other words, it’s time to head for the moon. Three days later the crew is in lunar orbit. A day after that, Armstrong and Aldrin climb into the lunar module Eagle and begin the descent, while Collins orbits in the command module Columbia. Collins later writes that Eagle is “the weirdest looking contraption I have ever seen in the sky,” but it will prove its worth.

ALARMS SOUND

When it comes time to set Eagle down in the Sea of Tranquility, Armstrong improvises, manually piloting the ship past an area littered with boulders. During the final seconds of descent, Eagle’s computer is sounding alarms.

It turns out to be a simple case of the computer trying to do too many things at once, but as Aldrin will later point out, “unfortunately it came up when we did not want to be trying to solve these particular problems.”

When the lunar module lands at 4:18 p.m EDT, only 30 seconds of fuel remain. Armstrong radios “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.” Mission control erupts in celebration as the tension breaks, and a controller tells the crew “You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue, we’re breathing again.” Armstrong will later confirm that landing was his biggest concern, saying “the unknowns were rampant,” and “there were just a thousand things to worry about.”

FIRST STEP

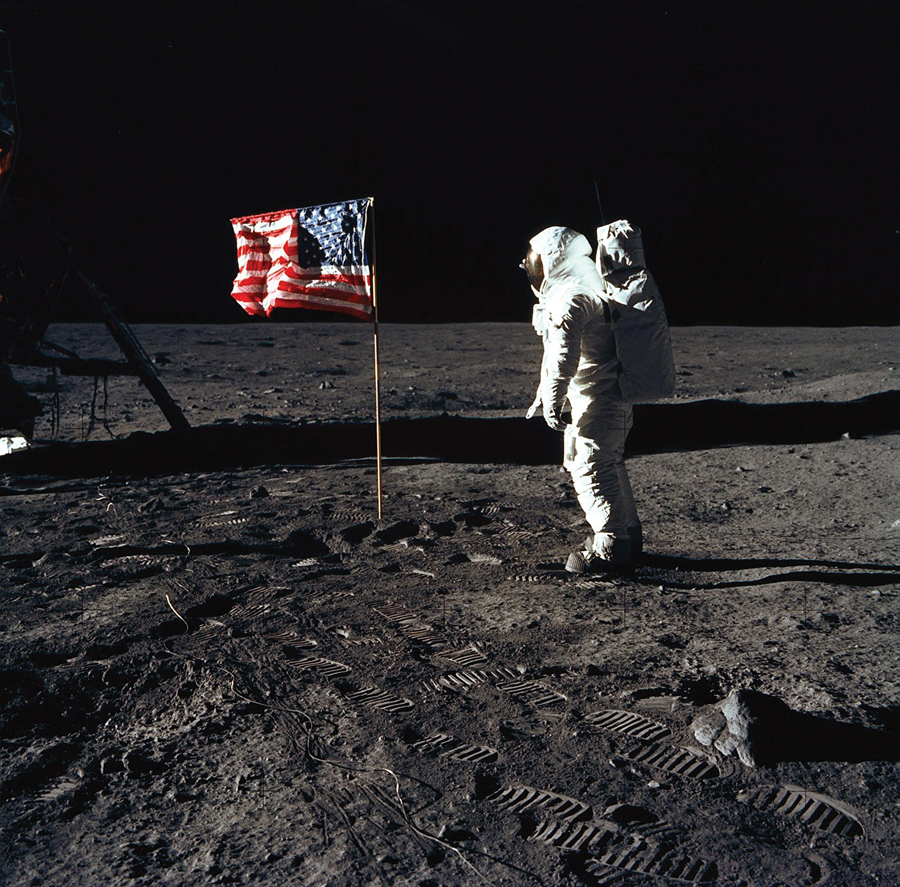

At 10:56 p.m. EDT Armstrong is ready to plant the first human foot on another world. With more than half a billion people watching on television, he climbs down the ladder and proclaims: “That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.” Aldrin joins him shortly, and offers a simple but powerful description of the lunar surface: “magnificent desolation.” They explore the surface for two and a half hours, collecting samples and taking photographs.

They leave behind an American flag, a patch honoring the fallen Apollo 1 crew, and a plaque on one of Eagle’s legs. It reads, “Here men from the planet Earth first set foot upon the moon. July 1969 A.D. We came in peace for all mankind.”

HEADING HOME

Armstrong and Aldrin blast off and dock with Collins in Columbia. Collins later says that “for the first time,” he “really felt that we were going to carry this thing off.”

The crew splashes down off Hawaii on July 24. Kennedy’s challenge has been met. Men from Earth have walked on the moon and returned safely home.

In an interview years later, Armstrong praises the “hundreds of thousands” of people behind the project. “Every guy that’s setting up the tests, cranking the torque wrench, and so on, is saying, man or woman, ‘If anything goes wrong here, it’s not going to be my fault.’”

In a post-flight press conference, Armstrong calls the flight “a beginning of a new age,” while Collins talks about future journeys to Mars.

Over the next three and a half years, 10 astronauts will follow in their footsteps. Gene Cernan, commander of the last Apollo mission leaves the lunar surface with these words: “We leave as we came and, God willing, as we shall return, with peace, and hope for all mankind.”

By Mary Alys Cherry

By Mary Alys Cherry