By Michael W. Gos

Enchanted Rock, Texas

If you spend any time at all in Hill Country, you have probably been to Enchanted Rock. The main reason most of us go there is to enjoy the view and the cool breezes from the top, or to learn why it is called “enchanted.” But how many of us think about the geologic processes that formed it? Sure, Texas Parks and Wildlife has pamphlets and maps with brief explanations of the process, but for the most part, who cares? We came here to take in the beauty. It has always fascinated me, for instance, that the rock has two false tops before you get to the actual peak. Just when you think you are about to reach the top, a new rise comes into view. An optical illusion, I guess. But beyond that, I didn’t give the formation much thought.

I was climbing the rock with my running buddy and his ten-year-old son. Being a city kid, as you might expect, the boy ran ahead of us, excited to be in this strange environment.

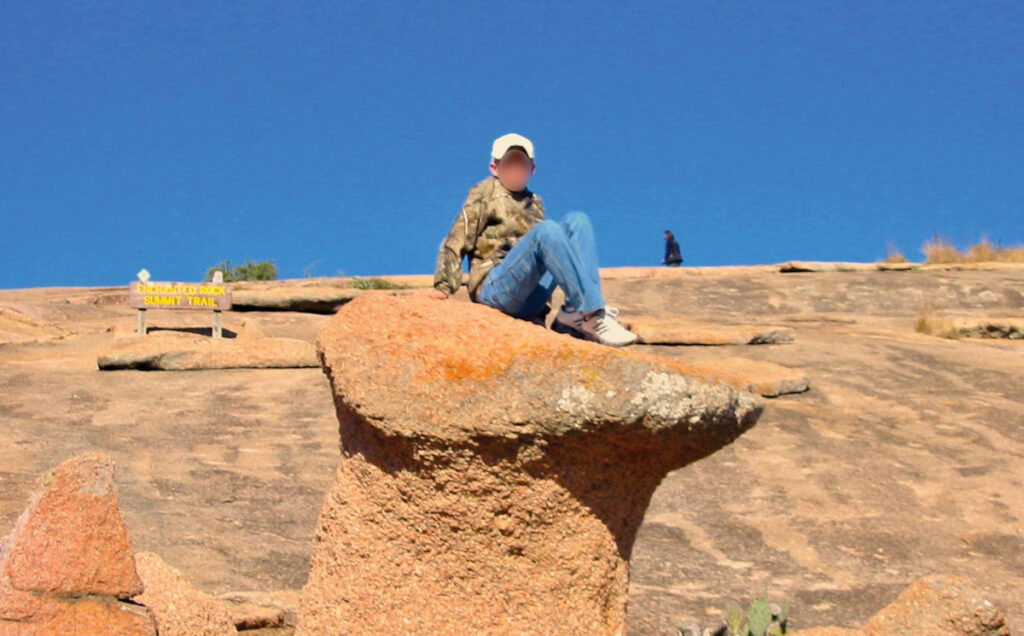

Then he discovered his first mushroom rock.

Like any kid, the first thing he had to do was to try to climb on top of it. But it was about eight feet tall. Unsuccessful, he moved on to another, smaller one, and this time he was able to climb up and sit on the cap. Flushed with success, his mind moved on to other things—why does this rock, and others like it, have such a funny shape? And like any kid that age, he asked me that question. My job was to formulate an answer.

Being an exfoliation dome, Enchanted Rock peels off layers of “skin” like an onion. As that happens, sometimes boulders are left. Because the top of the boulder is of a harder substance than the sides, water and wind erode the sides, leaving the unusual shape. Of course, for a ten-year-old, that is too much information. I would have lost him on “exfoliation dome.” Yet such an intelligent question deserves an honest answer—well, semi-honest anyway.

The process of education is in reality, a process of lying. At the very least, we leave out important information. When we teach grade schoolers about the structure of the atom for example, we identify three particles for them: neutrons, protons and electrons. We consider others such as quarks and bosons to be inconsequential for our purposes, so we leave kids with a simplistic, not quite accurate explanation. My job was to answer the boy’s question truthfully, even if not fully, and to encourage such questioning in the future.

I had him rub his hand along the surface on which he sat. I asked him how it felt. He replied that it was smooth and hard. Then I had him climb down and do the same on the side of the mushroom. His face lit up as he discovered little pieces of the rock coming off in his hand. I told him that, like his hand, the rain and wind take off small pieces. I knew he understood when he said “Then it will fall over some day.”

The main job of children is exploration and discovery. It is something they do naturally and something they are very good at. The fact is, they can be encouraged in this process or discouraged by the adults in their world. Sure, the questioning can get annoying sometimes, especially the most common one, “why?” But the way we respond can be critical to the rational and creative development of the child.

Unfortunately, it is a part of the human condition that as we get older, we tend to ask fewer questions. Maybe it is because as time goes on, we learn more and there are fewer things that puzzle us; but I suspect not. I think it is more a matter of changing our essence—of losing that inquisitive, discovery-oriented part of ourselves, of our human nature. That is sad; and we see the results of this change all around us.

Most artists (whether in painting, writing, architecture or music) do their best work young. As kids, we are all artists. As we get older, we get less and less able to create, to come up with new and unique solutions to the problems around us. But this is true in all of life, not just the creative arts.

When I think about some of our greatest accomplishments as a specie, I always think about the space program in the 1960s. No matter where you live in America, or even in the world, people recognize that our space program represents man at his best. While the Apollo 11 astronauts who made the first moon landing were 38 and 39 years old, did you know that the control crew of the Apollo 13 mission averaged just 29 years of age (McKie, The Guardian)? Do you remember how they were able to face every problem, every emergency, and immediately come up with a solution? I really wonder if a crew of 60-year-olds would have been able to match that performance.

We see maturing as a process of giving up childish ways and we view people who keep those ways as somehow ab(sub)normal. But whether we are talking about artists or scientists, the best performances seem to come when we are young, before we completely jettison our natural-born abilities of children.

I suppose there may be some cultural issues at work here as well. Other cultures tend to revere their elderly, to show them great respect and honor. But here, not so much. We tend to instead place increased value on youth. That in turn causes us to make a concerted effort to stay young, be it through diet, exercise or plastic surgery. This may not be a bad thing. With our emphasis on youth we have become a culture that stays young longer. But I wonder if we aren’t looking at the wrong traits in this quest for youth. Maybe if we paid as much attention to keeping our minds young as we do our bodies, great things could happen.

The longer we can stay young in our minds, the longer we can hang on to those traits of discovery and creativity we had as children, the more productive we can be.

I think we will be happier for it.

By Michael W. Gos

By Michael W. Gos

By Michael W. Gos

By Michael W. Gos