Photo by Michael W. Gos

By Michael W. Gos

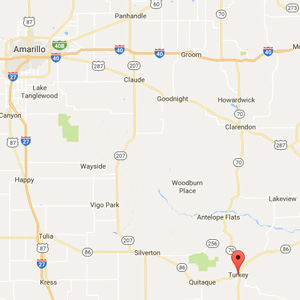

Terlingua Ghost Town, Texas

If you spend a lot of time in any place, even as a tourist, you get to know some of the people there and come to call them friends. I go to Big Bend country a lot, and when I am done with my day’s hiking, I head to Terlingua for some laid-back fun. As a result, I know quite a few people there.

I’ve talked to him for about seven years and this was the first time I’d seen him without his wife. He was sitting on the porch of the Trading Post when I pulled up.

“Hey Don, how are you doing?”

“Hanging by my finger nails, like the cat on the poster.”

“Where’s Jules?”

“Not sure; she and I split up a couple of months ago.”

That really took me by surprise. They seemed like the perfect couple. I never saw one without the other and they always seemed to be having fun together.

“What happened?” I asked.

“She wanted to get married; I didn’t. I guess she got tired of waiting. She said eight years was long enough.”

This was the first time I realized they weren’t married.

I went in and bought a beer and took it out to the porch. We talked for the next hour. He told me about how he was crazy about her and wanted to live with her for the rest of his life, but he refused to ever get married again. He said his divorce years earlier had turned him off marriage for good.

Apparently, that wasn’t an acceptable situation for her. I asked if he was really willing to lose her because of something that happened many years ago. He said he didn’t have a choice; he couldn’t marry again. That made me think about a time in my own life.

I remember the day like it was yesterday, and it ruled my life for the next 15 years. In my football days the coaches drilled into my head that my job on sweeps to either side of the field was to stay in the middle of the backfield. Under no circumstances was I to pursue the ball carrier. Then one day, it happened.

At the snap, the running back ran to the right as the quarterback dropped. The handoff was made and the play went away from me. Not thinking, I took off in pursuit. The ball carrier had a lateral head start of about seven yards, but in order to gain yardage he’d have to turn upfield. I was sure I could catch him; I had the angle. I was already past the center and in a dead run when I saw it happen. The running back handed the ball to the split end on that side, who reversed back to my left. The action froze me in my tracks!

Thoughts flew, but my body remained frozen. I knew I needed to turn back and pursue the play, but it took an eternity to get my rather large body to stop, turn and follow. Finally, word got to all appropriate body parts and I was running up the line again, this time to the left. It didn’t take long to realize that I wasn’t going to make the play. I looked ahead to the corner to see who was there to help, but the corner was empty. Only the left tackle and I were to be on that side of the field, and no tackle would ever catch a wide receiver. I looked up just in time to see the ball carrier run right over the spot I was supposed to be occupying. I could only watch as the play went all the way for a touchdown. I went back to the sidelines, chin against my chest.

“How many times have we told you to stay home on that one?” the coach yelled. “You think we tell you these things for our health? You have a (expletive) job to do here! We told you exactly what it is! How much sense does it take to do what you’re told? You cover on reverses! If you pursue, we lose!”

For days I ran that play over and over again in the theatre of my mind. I had always believed it was best to play inspired — that emotion and enthusiasm would win out over cold, calculated logic every time. Now it looked like, at least in some cases, cold, rational control was far more important. After all, football is a brain game. That is why the intricacies are so hard for most people to understand. But that day I took away a very important, and life-changing lesson. I learned that there are sound reasons for the things we are told to do.

For the next 15 years, that lesson stayed with me. I did what I was supposed to do, stayed within the limits I was given and lived a quiet life. If I had any ideas that could even be remotely considered “wild,” I would always bounce them off someone I trusted before acting on them —and it kept me out of trouble.

Then one day, about 10 years after I finished college, my mother and I had a serious discussion about what I wanted to do with my life. I had been drifting somewhat aimlessly for a long time. I told her what I really wanted to do was to go back to school, get a couple of advanced degrees and become a professor. She laughed and told me to get serious. That was a dream for rich kids, smart kids. She said I should go to work in the steel mills. With my degree, they would probably make me a foreman. That conversation made me start to question the wisdom of living my life “within the lines.”

Both the man at Terlingua and I had fallen into a pattern of letting ghosts from our past limit and even disrupt our lives today. Traumatic events can indeed sometimes have strong effects on us, but when they start to limit our possibilities, our futures, it is time leave them behind. It makes no sense to keep stumbling over objects that are behind us.

It took a couple of years to complete the change. It wasn’t easy; I had a lot of false starts, but I stayed at it and eventually I stopped doing what I was “supposed” to do, went on to get those degrees and to get that life I wanted.

I hope when I next go to Big Bend, Don will tell me he did the same.

By Michael W. Gos

By Michael W. Gos

By Michael W. Gos

By Michael W. Gos

By Michael W. Gos

By Michael W. Gos

By Michael W. Gos

By Michael W. Gos